A blog for Catholic men that seeks to encourage virtue, the pursuit of holiness and the art of true masculinity.

Sheen: The Real Definition of Mercy

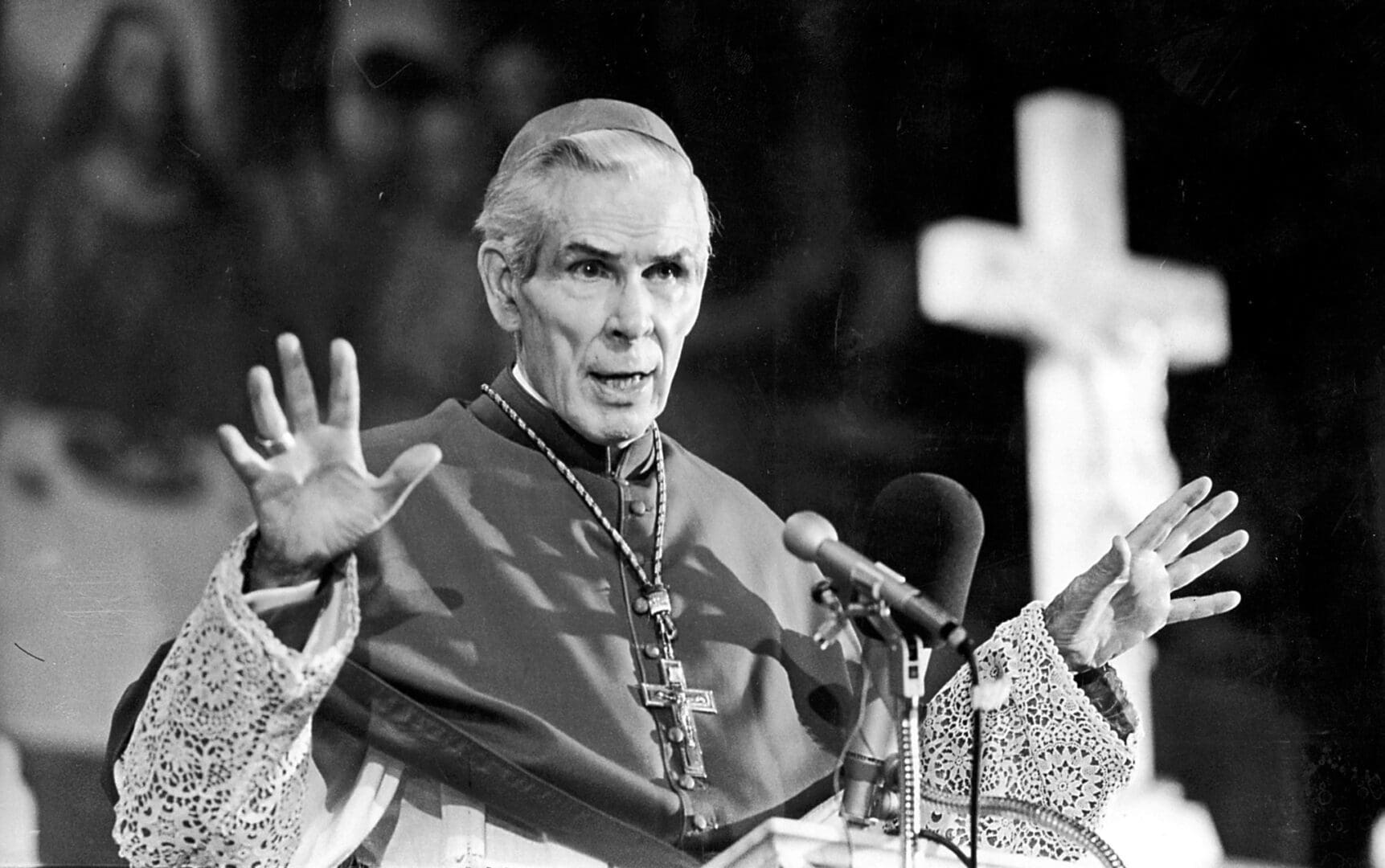

Occasionally on Fridays I will be posting excerpts from the writings of the great American bishop and media evangelist, Ven. Fulton J. Sheen. Call them #FultonFridays! Today’s excerpt is on the relation between mercy and justice.

As the world grows soft, it uses more and more the word mercy. This could be a praiseworthy characteristic if mercy were understood right. But too often by mercy is meant letting anyone who breaks the natural or the Divine law, or who betrays his country. Such mercy is an emotion, not a virtue, when it justifies the killing by a son of his father because he is “too old.” To avoid any imputation of guilt, what is actually a murder is called euthanasia.

Forgotten in all such mercy pleas is the principle that mercy is the perfection of justice. Mercy does not come first, and then justice; but rather justice first, then mercy. The divorce of mercy and justice is sentimentality, as the divorce of justice from mercy is severity. Mercy is not love when it is divorced from justice. He who loves anything must resist that which would destroy the object of his love. The power to become righteously indignant is not an evidence of the want of mercy and love, but rather a proof of it.

There are some crimes the tolerance of which is equivalent to consent to their wrong. Those who ask for the release of murderers, traitors, and the like, on the grounds that we must be “merciful, as Jesus was merciful,” forget that that same Merciful Saviour also said that He came not to bring peace, but the sword.

As a mother proves that she loves her child by hating the physical disease which would ravage the child’s body, so Our Lord proves he loved Goodness by hating evil, which would ravage the souls of his creatures. For a doctor to be merciful to a typhoid germs or polio in a patient, or for a judge to be tolerant of rape, would be in a lower category the as for Our Lord to be indifferent to sin. A mind that is never stern or indignant is either without love, or else is dead to the distinction between right and wrong.

Love can be stern, forceful, or even fierce, as was the love of the Savior. It makes a scourge of ropes and drives buyers and sellers out of temples; it refuses to give the courtesy of speech to moral triflers like Herod, for it would only add to his moral guilt; it turns on a Roman Procurator, boasting of Totalitarian law, and reminds him that he would have no power unless it were given him by God. When a gentle hint to a woman at the well did no good, He went to the point ruthlessly and reminded her that she had five divorces.

When so-called righteous men would put Him out of the way, He tore the mask off their hypocrisy and called them a “brood of vipers.” When He heard of the shedding of the blood of the Galileans, it was with formidable harshness that He said: “You will all perish as they did, if you do not repent.” Equally stern was He to those would offend the little ones with an education that was progressive in evil: “If anyone hurts the conscience of one of these little ones that believes in me, he had better been drowned in the depths of the sea with a mill-stone tied around his neck.”

If mercy meant the forgiveness of all faults without retribution and without justice, it would end in a multiplication of wrongs. Mercy is for those who will not abuse it, and no man will abuse it who already started to make the wrong right, as justice demands. What some today call mercy is not mercy at all, but a feather-bed for those who fall from justice; and thus they multiply guilt and evil by supplying such mattresses. To become the object of mercy is not the same as to got scot-free, for as the word of God says: “Whom the Lord loveth, he chastiseth.”

The moral man is not he who is namby-pamby, or who has drained his emotions of the sterner stuff of justice; rather he is one whose gentleness and mercy are part of a larger organism, whose eyes can flash with righteous indignation, and whose muscles can become as steel in defense, like Michael, of the Justice and the Rights of God.

From Way to Happiness by Fulton J. Sheen (Garden City Books, 1949).

This is one of the most clear and many explanations of mercy as a virtue that I have ever read. I enjoy writings that bring to speech for me things that I know, intuitively but cannot articulate. This article did that for me. Our Christian Catholic faith is often paradox. mercy and Justice appear to be just such a paradox, and yet they must go hand in hand. Sheen was a great man. Thanks Catholic Gentleman (Sam) for placing this wisdom in front of us men.

That was suppoed to be “Clear and “manly”…”

Hi Sam,

I think I might have founds two typos in this excerpt from Sheen. This sentence, which appears in the first paragraph, seems to be missing its proper ending: “But too often by mercy is meant letting anyone who breaks the natural or the Divine law, or who betrays his country.” I believe the sentence ought to finish as such: ” . . . Divine law, or who betrays his country, simply get away with such acts with impunity.” Otherwise the sentence doesn’t seem to make much sense.

Also, I believe the last line in the second to last paragraph ought to read, “is not the same as to go scot-free.”

Sheen, in my opinion, is one of the greatest Catholic writers (and speakers) of the modern era; just want to make sure his work is remembered as such and doesn’t float around online with any mistakes.

Thanks so much for your #FultonFridays. I really do enjoy these posts! Thanks!