A blog for Catholic men that seeks to encourage virtue, the pursuit of holiness and the art of true masculinity.

A Morning Mass

It is a Saturday morning. I wake while it is still dark and blindly shuffle into my clothes. My children sleep. The world is still as I step into the chill morning air to attend the early morning Low Mass at the Abbey of Our Lady of Clear Creek.

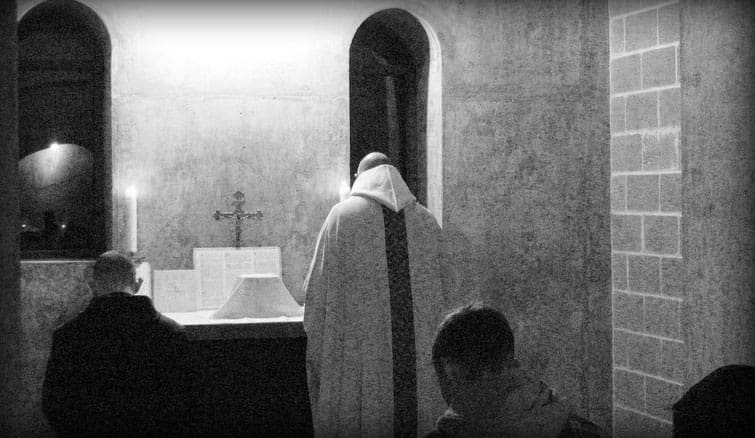

I arrive at the monastery while the moon still sheds its pale light in the sky, surrounded by a blanket of stars. It is dark inside the monastery, chill. Only a few dim lights illumine the blackness from above. Two candles are lit on a nearby altar, their flames dancing gently and casting a thin light on the brassy metal of gothic crucifixes.

Monks noiselessly appear from the darkness, their faces shrouded beneath ghostly white hoods. They take their places at the side altars dispersed throughout the sanctuary. This is the ancient way of concelebration—each priest-monk celebrating his own Mass, at his own altar, in unison with his brothers. Gold and white vestments shimmer in the half light as black-robed lay brothers shuffle busily around the altars, preparing them for the sacrifice that is to come.

Mass begins. The monk whose mass I attend signs himself and bends low at the waist. He whispers the words to the ancient prayer of contrition, the Confiteor.

Confiteor Deo omnipotenti, beatæ Mariæ semper Virgini, beato Michaeli Archangelo, beato Ioanni Baptistæ…quia peccavi nimis cogitatione, verbo et opere: mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.

I confess to Almighty God, to blessed Mary ever Virgin, to blessed Michael the Archangel, to blessed John the Baptist…I have sinned exceedingly in thought, word and deed: through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault.

The Mass begins as it will end: in near perfect silence. The priest gestures slowly, reverently, with movements at once opaque and pregnant with meaning. His is a silence of intimacy, a whisper of love. God alone hears his words.

The mysterious drama of the Mass is not lessened by this absence of audible words and music, as some might think, but rather heightened and intensified. Here unfolds the ancient and eternal Sacrifice, the world’s salvation. Here is a joy the world cannot comprehend, even finds strange and foolish. It is the delight of all the saints and all those who know it is the banquet of unending love. For the power of God comes not in a storm of excitement or nervous enthusiasm. It is a noiseless peace, the revelation of a God both hidden and humble; the marriage of heaven and earth in sensible signs.

In a moment of distraction, I look around the dimly lit church. Through the large windows at the end of the sanctuary I see the sky beginning to turn pink as the molten orange globe of the sun begins its ascent. Monks silently gesture at each altar in the growing light, carrying on their hidden conversation with God.

How far it all seems from the noisy bustle, the hungry discontent of the outside world. Here is a peace few will know. And yet, it seems to me that it is this very place of peace that keeps the world on its axis. Without these prayers, without this sacrifice of praise, without the oblation of these monastic lives, the world very likely would have ceased to exist long ago, drowned and destroyed by the sins of men.

There is a pause, and then the priest begins the solemn prayer of the preface.

Sursum corda. Habemus ad dominum.

Gratias agamus Domino Deo nostro.

Dignum et justum est.

Vere dignum et justum est, aequum et salutare, nos tibi semper et ubique gratias agere: Domine sancte, Pater omnipotens, aeterne Deus:…

Lift up your hearts. We have lifted them up to the Lord.

Let us give thanks to the Lord our God.

It is right and just.

It is truly right and just, proper and fitting for our salvation, that we should always and everywhere give You thanks, holy Lord, almighty Father, eternal God…

Thanksgiving. It is the heart of life. It is what we, and all creation were made for. Our hearts will always ache with emptiness until we discover the secret of all contentment, the power of praise.

The Sanctus is prayed. Then begins the ancient prayer, the canon of the Mass, unchanged for centuries and considered by some liturgical scholars to be the most ancient liturgical prayer in existence, dating back to the very earliest days of the Church. Names of martyrs are mentioned, men and women like Clement, Anastasia, Lucy.

These early martyrs were not written into this prayer as an ancient memory, but rather because they had died recently and the Church was remembering them and asking for their intercession. But because this prayer has remained nearly unchanged, we still remember their names today. An extraordinary fact.

The consecration approaches, and an even greater silence seems to descend on the cold stones of the abbey walls. The priest leans over the altar, whispering the most powerful words in the universe, the words of consecration that transform ordinary bread and wine into the body and blood, soul and divinity, of the Eternal Word, Jesus Christ.

HOC EST ENIM CORPUS MEUM.

For this is my body.

HIC EST ENIM CALIX SANGUINIS MEI, NOVI ET AETERNI TESTAMENTI : MYSTERIUM FIDEI : QUI PRO VOBIS ET PRO MULTIS EFFUNDETUR IN REMISSIONEM PECCATORUM.

For this is the chalice of my blood of the new and everlasting covenant, a mystery of faith: it will be shed for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins.

It is a wonder that the walls do not quake at such words. And yet such is the humility of God that he allows this miracle to occur in stillness. For the voice of God is not heard in fire and storm or in great commotion, but in humility and silence.

The priest genuflects in front of the mysteriously transformed elements. And then something wonderfully unexpected occurs, a startling coincidence of time. As the priest elevates the pale host high above his head, the rising sun appears just at that moment through the windows at the far end of the sanctuary. It appears directly behind the host, as if illuminating the hidden reality that is there. The light blinds me, and I cannot gaze for long. But the effect is profound. The God whom the angels cannot gaze upon is hidden in this host. How quickly I forget it, and how casually I receive him. Yet, for one dazzling instant, it was is if I could see his blinding glory shine through, like St. Paul on the road to Damascus.

Finally, the moment of communion draws near. Striking his breast, the priest says three times: Domine, non sum dignus… Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed.

This beautiful prayer was not simply written by a holy man long ago. It is directly from the words of the Gospel. Even more profound, they were spoken by a Roman Centurion, a battle-hardened man of worldly power. Doubtless he had seen many battles and defeated many foes to achieve his rank. Doubtless he was courageous and feared no man. And yet, he bowed his knee before a wandering prophet from a backwater town.

This commander of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of men, saw the greatness of Jesus. He knew he was not simply a rabbi, a teacher. He knew he had authority, and that this authority came not from men, but from God himself. He saw in him the Savior of mankind and the Son of God. And he could not but humble himself before him, bowing his knee and declaring his unworthiness. Domine, non sum dignus. Lord, I am not worthy.

It is this same humility that is the strength of every true man. For before God, we are all nothing but grass—even the strongest of us. Yet, acknowledging our humility before the Lord is not degrading. It does not diminish us. Paradoxically, there is something in humility that enlarges the heart, that leads to freedom and genuine strength. We must bow the knee to become our true selves, to become men of full stature. For when we are weak, it is then we are strong.

The Mass draws to a close. The priest says the final prayers of blessing and we are dismissed. I step in the bright clear air of the breaking morning. Birds sing, seemingly continuing prayers of praise with their cheerful melodies. Joy fills my heart, and peace too. Though I am the most unworthy of all, I have received the Lord of Life—and have been healed.

Beautiful!

Point of correction- St. Paul was traveling to Damascus, not Emmaus. There were two disciples traveling to Emmaus, and they may have been a husband and wife (the Greek word used translates into ‘argue,’ in both a literal and philosophical sense).

Do you live in Clear Creek?

Enriched!

Simply wonderful. The most memorable mass I ever attended was one just like this at Clear Creek Abbey.