A blog for Catholic men that seeks to encourage virtue, the pursuit of holiness and the art of true masculinity.

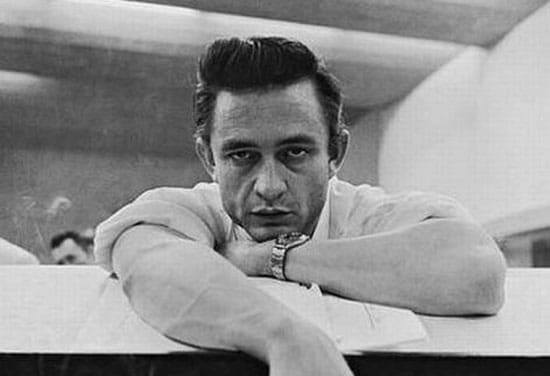

Digital Masses and Johnny Cash on the Pain of Lonely Sundays

Note: This is the opening of the forthcoming issue of Sword & Spade. It is being published here exclusively because of its ties to an upcoming Sunday that is potentially without Mass.

As this issue nears printing the coronavirus is forcing many into “social isolation” to slow the pandemic. Whatever your opinion of such measures, there is the real possibility that many feasts days will go by without true feasting, without people gathered to celebrate. Easter is approaching, the feast of feasts, but we also have various saints, including St. Patrick and St. Joseph in the third week of Lent, with the Annunciation coming March 25th. There is a real chance that heaven will be rejoicing as catechumens enter the Church at the Easter Vigil, yet the church will be empty and void of a corresponding celebration.

This issue, which has festivity as a focus, seems ironic in a time when we cannot be together. But maybe our hindered celebrations will help us recalibrate our habits and dispositions. Yes, we know, as St. Paul says, that we can “rejoice in the Lord always,” but true festivity (feasting) is stunted, at the least, when we are alone. Being denied access to something we hold so dear as Mass, and perhaps so complacently, can indeed remind us that our hunger for God cannot be quenched by anything or anyone other than God. And the festivity that the Church literally commands by obligation on Sundays and Solemnities might just become missed all the more by an obligation to stay away.

In other words, Sunday loneliness might be a good tonic for the rote indifference and un-festiveness we might have failed to notice.

Sunday, Hungover and Alone

I can’t help but think of the wisdom and poetry of Johnny Cash. In his song Sunday Morning Coming Down he describes the emotions felt when encountering the festive togetherness of a community on Sunday morning. He wakes uneasily, because he “smoked his brain the night before” and had clearly been drinking: “…no way to hold my head / That didn’t hurt.” For breakfast he has a beer that was good enough to have “one more for dessert.” Then he puts on his least “cleanest dirty shirt” and goes for a walk outside in an obviously tight community, and that’s when the real pain begins.

His encounter with Sunday isn’t as one participating, but as one observing from the outside. His metaphysical misery – which is much worse than the physical hangover – begins when he smells some chicken frying, grows when he leans in to hear a Sunday school class singing, and seems to pierce the heart fully when he takes special note of a man living paternally: “In the park I saw a daddy / With a laughing little girl / He was swingin’.” He remembers the taste of fried chicken on a Sunday; he remembers the songs of church; and perhaps he even recalls the joy a father receives when the whole world melts into the joy of a loved and attended child laughing on a swing with perfect innocence and presence – because of your strength applied gently and ably.

Those memories, however, are clearly fading as he moves further from their sources – “The disappearing dreams of yesterday,” as he calls them, something “[that] I’d lost somehow / Somewhere along the way.” All he encounters on that Sunday morning reveals how unfulfilling his current lifestyle is. “’Cause there is something in a Sunday,” he says, “That makes a body feel alone.”

Realizing his emptiness and remembering a better past, however, doesn’t draw him back home, but makes him long to return to the “high” of the previous night that he is “coming down” from: “On the Sunday morning sidewalk / Wishing Lord that I was stoned.” And, if he can’t have that, he might as well be dead, because “there’s nothing short of dying” that is as torturing as sensing Sunday joy but lacking all possession of it.

Virtual Mass and True Festivity

I don’t know if I’ll be forced to watch Mass on a screen, but if that happens I hope it inspires a longing for some of the essential elements of Christian worship like in-the-flesh celebration, sacrifice, and society (the Church, after all, is a society). And, perhaps seeing Mass on a screen will help us all to see the pseudo-community of media for what it is, a form of social distancing slyly sold as sociability. Like Cash’s character walking down the street on Sunday, looking in from outside, we’ll be looking at Mass from the outside. We’ll feel the distance, unless we’ve become so dehumanized to think “sites” and “places” on the internet are actually sites and places.

It also appears this whole episode of varying intensities of quarantine will be crippling to many sectors of the economy (disposable bathroom products exempted). In other words, in the midst of much worry – especially for providing fathers – we will likely face some forced considerations of life’s essentials, those things most dear to us, or things that should be. I suspect that alongside the real challenges of money and bills, our time away from “the grind” might also awaken us to the good things in life we forget to be grateful for and festive about – like fried chicken, songs, and swinging our children.

In that vein, perhaps the topic of this issue is strangely suited for our times – we could even call it plain ironic. The main article that inspired this issue was a story from two small-business owners that voluntarily closed for the Solemnity of the Assumption. This was a financial and practical sacrifice, which means it was a true feast; one cannot feast without killing the fatted calf, without the loss of something. In the spirit of Cash’s song, my contribution compares the world’s false festivity (partying) with true Catholic feasting. As a needed temper to festivity’s potential excess we have more from a Byzantine priest about the need for fasting in order to feast and Cardinal Newman on chastened celebration, the wisdom of Lent then Easter. We also have an Olympic-style weightlifting coach to remind us that the long path to greatness (analogous to the triumph of something worth celebrating) comes only by the slow, deliberate focus of endurance and discipline. As is the custom of this magazine we have excerpts from Church documents and saints, and I hope you find particularly edifying the selections from St. Augustine’s Confessions as it follows his conversion from party-boy to prolific pastor.

Without God, life always tends toward despair or distracting indulgence. In a purely material world there really is no good reason to be festive. In our current climate it certainly seems that we’ve grown in fear of that which kills the body, but not the soul. Festivity, which nourishes the soul and is the soul’s affirming response to life’s essential and unassailable goodness, is something we Catholics do by nature. It looks like the world is going to need that in a special way during this coming Easter season.

Jason Craig works and writes from St. Joseph’s Farm in rural North Carolina with his wife Katie and their five kids. Jason is the author of Leaving Boyhood Behind and Director of Program and Training for Fraternus, a mentoring program for young men, and holds a masters degree from the Augustine Institute. He is known to staunchly defend his family’s claim to have invented bourbon.

COMMENTS

Reader Interactions